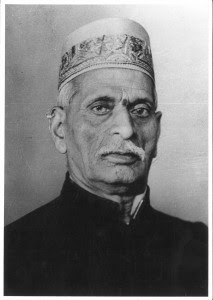

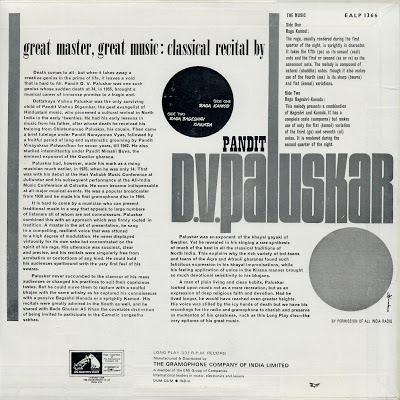

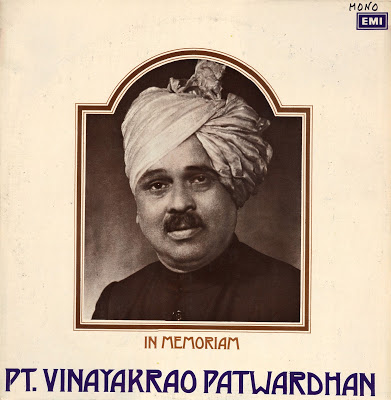

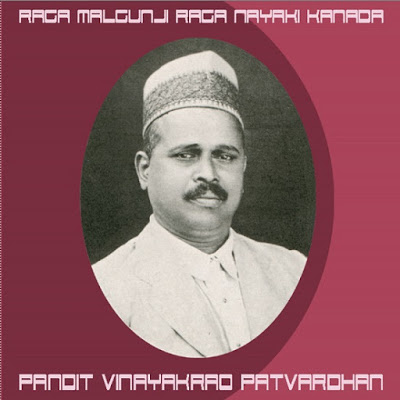

VINAYAKRAO PATWARDHAN: FAMOUS MUSICIAN & DEDICATED MISSIONARY-- by P.C. Jayaraman and S. Janaki

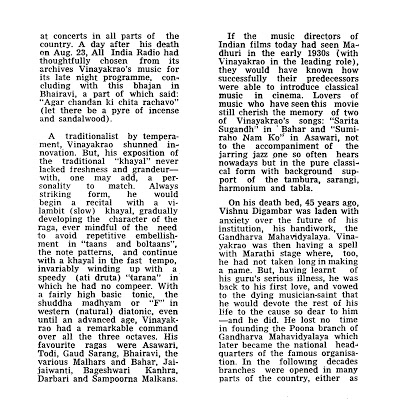

[The year 1998 was host to the birth centenaries of many stalwarts of music. Among them was that of Hindustani vocalist Pandit Vinayakrao Patwardhan. The following commemorative article was written by Senior Editor P. C. JAYARAMAN with Deputy Editor S. JANAKI. The authors are indebted to the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in New Delhi for making available source materials and photographs. Its former Principal, the late Vinaychandra Maudgalya, was a disciple of Vinayakrao Parwardhan.]

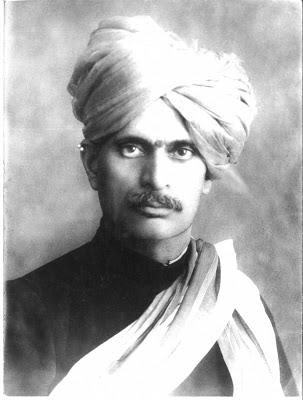

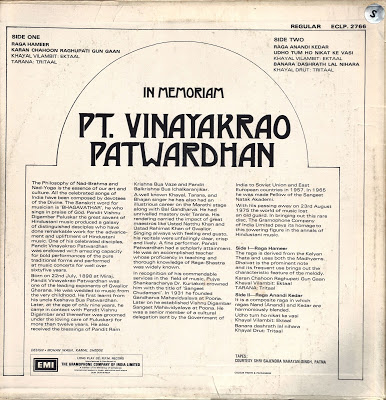

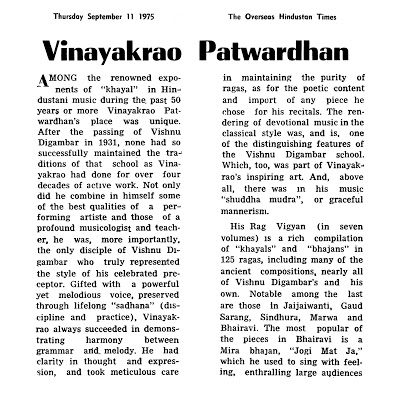

Vinayakrao Patwardhan was a well-known figure of his times with a multifaceted personality. An illustrious disciple of the legendary Vishnu Digambar Paluskar who devoted his life to the promotion of Hindustani music, and a gurubhai of such eminences as Prof. B.R. Deodhar, Narayanrao Vyas and Omkarnath Thakur, he had a very successful singing career. For about 52 years (from 1923 to 1975), he was one of the famous musicians in the Hindustani music concert arena. He was successful also as an actor-singer in Marathi theatre where he partnered the renowned Narayanrao Rajhans. He also contributed significantly to the teaching of music, as a member of the faculty of music schools and a private teacher of a horde of students. Furthermore, a music missionary like his great guru, he also authored books on music. Last but not least, he was an able administrator and a man of culture.

Early life

Vinayakrao was born in Miraj, in what is now Maharashtra, on 22 July 1898 in a well-to-do, middle class family of Dasagranthi Maharashtrian brahmins. He was named Vinayak because he was born on Ganesh Chaturthi day.

Vinayakrao's mother passed away in 1902 and he lost his father, Narayanrao, as well a few months later. His paternal uncle took on the responsibility of bringing him up. Theirs was a joint family which was characterised by religious faith, simplicity and discipline. Vinayakrao imbibed these qualities in full easure and retained them till the end.

Music, however, was not part of the family heritage, although two of his paternal uncles were musicians. One of the uncles, Gurudev Patwardhan, was a pakhawaj player and taught percussion - playing at a school established by Vishnu Digambar. The other, Keshavrao Patwardhan, a disciple of Balakrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar, taught music at the Ganesh Sangeet Vidyalaya. It was in this school that Vinayakrao started learning music in the year 1905.

It was Vinayakrao's good fortune that, about this time, Vishnu Digambar Paluskar was scouting for musically inclined youngsters, who could later help him in his chosen mission of propagating music. His eyes fell on Vinayakrao with whose family he was acquainted. Further, the Patwardhan family was only too happy to send Vinayakrao away from Miraj, which was often scourged by epidemics.

By another stroke of luck, the ruler of Miraj, Gangadhar Pant Patwardhan, aka Balasaheb Mirajkar, came forward with an offer to pay a stipend of 16 rupees a month to enable Vinayakrao to study at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Lahore.

The programme offered by the vidyalaya was divided into two parts: the first was the Sangeet Pravesika course (four years) and the second, the Sangeet Praveen course (five years). While the academy naturally placed emphasis on musical training and presentation, it attached importance also to the all-round development of each student's personality, physical health, personal hygiene, dress and good conduct.

Vinayakrao studied at the Lahore institution only for a year or so - till August 1908. For, when Paluskar established another branch of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Bombay in September that year, he brought the lad from Miraj with him to the Gateway City. It was in the Bombay saakha or branch of the Mahavidyalaya that Vinayakrao further pursued the academy's programme of studies. He completed the Sangeet Pravesika course in 1911 and continued on till 1914.

During these six years, Paluskar often personally taught Vinayakrao and some of the other disciples, between 10 o'clock and midnight, how to sing alap, taan and boltaan properly. Once, when Paluskar developed acute pain in the eyes, Vinayakrao stayed up all night giving warm fomentation treatment to his guru's eyes. While this provided much relief to the guru, there was a bonus dividend for the dedicated disciple: he got the exclusive chance to learn a bandish _Ya bana byahan aayaa_ in Devagiri Bilaval!

During his study at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Bombay, apart from learning and teaching music to junior students, Vinayakrao was also assigned various tasks. He had to assist in the maintenance of the school building and the garden and the work of the press division; play the cashier's role; and also assist Sankarrao Vyas in the co-operative store. This experience helped him later in the discharge of administrative responsibilities.

Vinayakrao obtained the Sangeet Praveen diploma only in 1919, almost 12 years after his enrolment as a student of the institution in Lahore. The reason given is that the ruler of Miraj had stipulated, while agreeing to give him the stipend to study at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya, that the lad should return to Miraj in 1914 and spend the next three years honing his musical skills. And Vinayakrao had to fulfil this part of the agreement. Paluskar wanted him to utilise this period to polish, with the guidance of Balakrishnabuwa Ichalkaranjikar (1849-1927), the bandishes he had already learnt and also write them down in notation. While he did all this, Vinayakrao strengthened his wings further by giving recitals before the ruler of Miraj, who continued to show interest in the progess being made by his protege, as well as at temple festivals. In 1917, he resumed his studies for the Praveen diploma in Bombay and completed the same two years later.

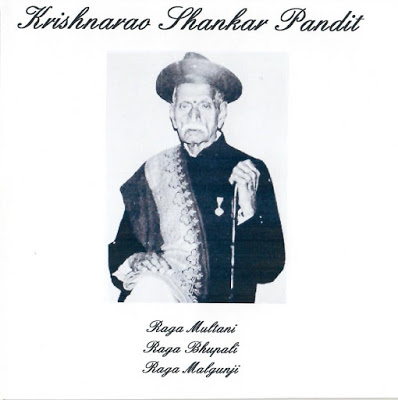

The time he spent with Ichalkaranjikar was indeed most fruit- ful. From this master, he learnt many rare bandishes of the Gwalior gharana, in raga-s like MaIgunji, Gunji Kanada, Malav, Samant Kalyan, Gandhari, Devagandhari, etc. Altogether he learned some 150 cheej-s from him. He also played the tambura in the master's concerts and this opened up another window of opportunity - to learn by observation. He was lucky to have the personal guidance of Ichalkaranjikar for six years, but he kept in touch with him even later.

While he was in Miraj, Vinayakrao had the opportunity also to listen to the music of Rahmat Khan, the court singer in the tiny princely state of Kurundavad which was quite close to his home town. He was particularly impressed by this maestro's style of rendering the tarana and learnt several tarana-s from him. Luckily he was also called upon to play the tambura in several of Khan Saheb's concerts and this afforded him a fine chance to learn many nuances through observation.

Rahmat Khan (1852-1922), an exponent of the Gwalior gharana, extolled as Bhugandharva, was known for the use of the words dil-dil in adroit ways while singing tarana-s. Vinayakrao changed the words to dir-dir when he sang the tarana-s. He came to be regarded in time as a master tarana-singer.

Another musician who had an impact on Vinayakrao's musical development was Bhaskarbua Bakhle, whose greatness lay in the fact he had assimilated three streams of musical tradition and developed an attractive style of his own. The youngster is reported to have attended as many as 200 of Bhakle's performances and also played the tambura for him in many of them. Through keen observation he noted and absorbed many lessons, such as the desirability of projecting a pleasant countenance on stage and encouraging his sidemen, as well as the importance of the proper placement of swara-s in each raga.

Vinayakrao himself stated later in his life that he learnt the art and nuances of concert-singing from his guru Vishnu Digambar and the art of pleasing the rasika and creating the right ambience in classical music concerts by observing him, as well as Rahmat Khan, and Balakrishnabuwa over a period of 8 to 12 years, as he played the tambura for their recitals.

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar (1872-1931) was a great and unique figure in Hindustani music. He was totally devoted to Hindustani classical music and its propagation. His aim was to bring it to the common man. He also worked to elevate the status of musicians. For these reasons, he bent his efforts to implement a plan to transform music into a well-loved and respected art; to establish music schools in which knowledge would be transmitted without holding anything back; and pick up children and train them to be musicians and music teachers with character. Accordingly, he picked select students of the Vidyalaya who he believed had the aptitude and the potential to become musical missionaries. They had to be students in residence for seven to nine years who had received intensive training in music. They had also to be qualified to assist in teaching junior students. Vinayakrao Patwardhan fitted into this scheme nicely and therefore, without any hesitation, Paluskar recruited him to serve the mission of propagating Hindustani music, along with others like Govindrao Desai, Baburao Gokhale, N.M. Khare, Vamanrao Padhye, Sankarrao Pathak, Omkarnath Thakur, Narayanrao Vyas and Sankarrao Vyas. These handpicked students, serving later as music missionaries, helped in the growth of a number of kaanrasiya-s or rasika-s through the movement spearheaded by Vishnu Digambar, which was also called the Vishnu Digambar Sangeet Andolan.

Vinayakrao's gracious manners and his devoted service to Paluskar led his classmates to call him endearingly as 'Nit namo', which was actually the first words of a famous bandish.

More than a decade later, in 1932 to be exact, Vinayakrao started learning music from Ramakrishnabuwa Vaze as a gandabandha (formal) disciple. According to B.R. Deodhar [Pillars of Hindustani Music], Vaze (1871-1945), an accomplished musician, was unassuming and generous and completely free from jealousy or hate. Yet he would avoid teaching the numerous raga-s and bandishes he knew, even after insisting would-be learners should become his gandabandha disciples first, saying they were not good enough to learn them. To quote Deodhar again: "Occasionally, when he happened to be in a generous frame of mind, he would part with some of his learning but the generous mood was usually short-lived, and his original secretiveness would rear its head."

It was when Ramakrishnabuwa, during one of his concerts, said he did not know anyone who was worthy enough to share his secret hoard, that Vinayakrao vowed to himself he would crack the safe, as it were, by becoming an accredited apprentice of the maestro. But he laid down terms too. He insisted that the gandabandha ceremony should be a quiet affair; with Vazebuwa agreeing to this condition, it was performed in the premises of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya. At the concert after the ceremony, Vinayakrao refused to sit with the tambura behind his new guru; instead he sat with the audience and listened to him. Furthermore, Vazebuwa had to come to the Vidyalaya to teach Vinayakrao. Although the arrangement did not last too long, Vinayakrao did manage to learn raga-s like Malativasant, Bhankar, Bhatiyar, Khat, Nand, Desi and Jayant Malhar from Ramakrishnabuwa Vaze. This itself was a feat, compared to achievements of other talented musicians with a similar ambition. Apparently, only two - Haribhau Ghangrekar who was with Vaze for many years, and the master's own son Shivrambuwa - really managed to learn many bandishes from this generous miser.

Though essentially a vocalist, Vinayakrao also learnt to play the harmonium, the tabla, the jalatarang, the taar-shehnai, the sitar And the violin. He had acquired, too, some familiarity with the basics of Kathak, the dance-form. He had also picked up the rudiments of composing and printing as he and some of the other disciples of Vishnu Digambar were involved in the printing of books on music. (Between 1917 and 1922 Vinayakrao helped his guru publish the magazine Sangeetaamritpravaha).

Teacher

Vinayakrao Patwardhan excelled not only as a student but also as a teacher. His stint as a student at the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya had itself provided him - after he had completed the Pravesika course - with opportunities of teaching the junior students. After this and on his return to Miraj, at the young age of 16, he became a teacher at his old alma mater, the Ganesh Sangeet Vidyalaya. He brought to it the experience gained by him in Gandharva Mahavidyalaya and laid emphasis on strict discipline, concentrated study, proper syllabi for the courses, use of text books on music theory, writing music in notation and a system for examinations - all modelled on what prevailed in Gandharva Mahavidyalaya. Not surprisingly, the school attracted many youngsters, among them one who would later become very renowned, Prof. B.R. Deodhar.

In April 1921, Patwardhan joined the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya in Nagpur as its Principal on a salary of 60 rupees a month, with an allowance of 16 rupees for food. This post he held till May 1922. He was very popular in the institution where he was known as Buasaheb. He also taught music to children of well-to-do barrister families. But the vidyalaya was facing financial difficulties, with large outstanding debts incurred for meeting the cost of constructing a new building. Paluskar issued orders that the teachers should retain only 30 rupees from their pay and donate the balance for the upkeep of the school. The teachers, many of them now married, found it very difficult to manage with just 30 rupees a month. This was the time between the demise of Patwardhan's first wife in 1922 and his remarriage 30 months later, in June 1924, to Radhabai, daughter of Govindrao Marathe. His relatives were asking him to remarry. On the other hand, Paluskar took the view that, rather than remarry, Vinayakrao should devote his life singlemindedly to the service of the vidyalaya. Faced with these strains, Vinayakrao, now about 25 years old, parted company with Vishnu Digambar with whom he had spent about 15 years. He went back to Miraj and then on to Kolhapur. This was a turning point in his life.

Career on Marathi stage

Vinayakrao Patwardhan's uncle Harikrishna Patwardhan lived in Kolhapur. Though a homoeopath by profession, he was an ardent music and drama enthusiast. He was very fond of Vinayakrao who, he thought, should become an actor - which implied singing as well - in a good, popular stage group. Musical theatre had by then become very popular in Maharashtra. Characterised by the interposition of classical and semi-classical songs between parts of dialogue, the theatre had a large number of very famous singer-actors, the most notable among them being Bal Gandharva of the Gandharva Natak Mandali.

Bal Gandharva was among those who attended Patwardhan's second wedding. He was then on the lookout for a good actor with handsome features and an impressive personality. He himself used to play the female lead roles in his plays and wanted a male to act and sing opposite him. His attention fell on Vinayakrao and he tried to persuade him to join the Mandali.

The Mandali was a prestigious institution and it was no easy task for a greenhorn in acting to find a place in it. Reportedly, Patwardhan was the only person ever recommended by Bal Gandharva for recruitment as an actor by the Mandali. Yet Patwardhan was reluctant to accept the offer. Firstly, he was not sure he had the credentials to be a good actor. Furthermore, his main interest was in music in which he was well trained. But the economic factor now became important. Having had no formal education, he had no hope of finding a regular job. At this time, he did not have the backing of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya and it was more difficult to get concert opportunities. He was also unable to find enough disciples whom he could teach. Too, he was apprehensive that Paluskar would frown on his joining the stage as an actor. But his uncle and Bal Gandharva took it out of his hands and went directly to Paluskar with their proposal. Though initially opposed to the idea, Paluskar gave his approval after he was convinced that a career on the stage would not interfere with Patwardhan's concert career. But he did so rather reluctantly yet because he was afraid that a career in the theatre might affect Vinayakrao's personality and behaviour.

In the event, Vinayakrao joined the Gandharva Natak Mandah in August 1922 on a monthly remuneration of 60 rupees. This association with the stage lasted 10 years. Aiding him in his success on the stage was the fact that Marathi natya sangeet of this period had a classical flavour. In fact, many in audiences were there to listen to the songs rather than watch the plays.

Bal Gandharva was very fond of Vinayakrao and respected his steadfast devotion to classical values in music, his character and his way of life. He later raised his salary to 160 rupees a month. This of course led to some envy among his fellow artists. Some of them did not anyway regard Patwardhan's Gwalior gharana way of singing highly.

Vinayakrao made his debut on the Marathi stage as Narada in the play titled 'Saubhadra', within a month of his joining the Mandali. The play was staged at the New Elphinstone Theatre in Bombay. The character of Narada demanded that the person playing the role should be a good singer and have enough histrionic abilities to project a jovial countenance. Vinayakrao was a good singer but he was by nature of a serious disposition. A critic is said to have remarked that, as Narada, Vinayakrao was overcome by fear. The youngster showed his concern for doing well in whatever he did by taking instruction from Ganpatrao Bodas in Sangli whom he visited from time to time.

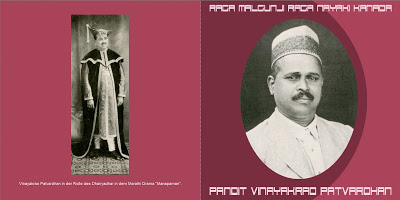

Vinayakrao went on to act in many popular plays, like 'Draupadi', 'Ekacha Pyala', 'Kanhopatra', 'Manapaman', 'Menaka', 'Mrichcha- katika', 'Nandakumar', 'Sakuntala', 'Samsayakallol', 'Sapasambhrama', 'Swayamvar' and 'Vidhilikhit', which were staged in several places. With his strong voice, which had a rich timbre and swara-suddha, he soon came to be regarded as one of the famous triumvirate of the stage, along with Bal Gandharva and Master Krishnarao. At the request of Bal Gandharva himself, he set to music the hero's songs in some plays. This in itself was an honour, as the Mandall had on its rolls eminent music directors like Bhaskarbuwa Bakhle and Govindrao Tembe. For about 10 years, he held an important place on the Marathi stage, despite having to compete with the great Bal Gandharva himself. The latter incidentally played the heroine in the plays in which Vinayakrao starred as the hero.

Some specialities of natya sangeet which Vinayakrao incorporated in his singing, included the use of aakaara phrases and the use of drut taan-s. He, however, did not like to take the liberty of using the graces (laalityapoorna gaayan) in his singing roles.

Vinayakrao had promised Paluskar that he would continue to give classical music recitals even while performing for the Mandali. And he did keep his promise. He also taught music to Vishnu Ghag and Janardhan Marathe, two young members of the cast of the Mandali, for nine years beginning in 1922.

Vinayakrao was one of those who stayed away from the pleasures usually associated with the world of drama in those times. In fact, he would not even drink tea. In spite of all this, Paluskar could not really reconcile himself to the fact that one of his favourite students was now member of a drama company. Accordingly, he had instructed his students not to allow Vinayakrao inside the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya. However, Vinayakrao was not deterred by this. Once when he was visiting Bombay, he went straight past the protesting students to meet his guru. Paluskar was initially angry but, when the visitor told him he was just the same old Vinayak and that he had abstained from drinking and other bad habits, he was appeased and the guru-shishya relationship was soon back on the old footing. In fact, in 1926, Paluskar advised Vinayakrao to bring out a book of natyageet-s, with notation, in order to propagate this genre of music. Vinayakrao agreed to do so with alacrity and 3000 copies of the first edition of _Natya Sangeet Prakash_, Part 1 was published in 1930. In 1932 he wrote Maharashtra Sangeet Prakash and then some more books.

Return to first love

Vishnu Digambar Paluskar died in August 1931 and this caused Patwardhan to ponder over what he was doing. His great devotion to his guru filled him with self-doubt and he felt that the time had come to leave the stage and return to his first love: music and its propagation. So he bade goodbye to the Mandali though he did act in a play one more time many years later. This was in 1971, on the occasion of the death anniversary of Bal Gandharva; he played the lead role in 'Sangeet Samsayakallol'.

There was a meeting of all the gurubandhu-s on 30 and 31 December to consider how best to carry forward the work of Paluskar. Vinayakrao and the others decided to establish what was called the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya Mandal, linking the vidyalaya-s in different places. Vinayakrao was elected to serve as its first President.

This apart, Patwardhan set about founding a music school - a new Gandharva Mahavidyalala - in Pune. He had to start from scratch. After a building was located, he launched the academy in May 1932. The launch was a grand event, presided over by the Editor of Kesari, N.C. Kelkar. Leading luminaries of the city were present. Vinayakrao and his disciples rendered the bandish _Param vimal tujhe charan_ in raga Patdeep. He followed it up with a speech in which he waxed eloquent about the form, greatness and scope of Hindustani music and laid emphasis on the need to set up the school for its propagation. He voiced the view it was his moral duty to spread Indian culture, namely, Indian music.

Vinayakrao immersed himself in the task of running the school, which was quite difficult in the early years. He managed to procure four tambura-s and two harmoniums along with a few carpets. He arranged for the classes to be conducted on the third floor of the building. The small staff consisted of Vinayakrao's disciples, Vishnu Ghag and Janardhan Marathe. His own salary as Principal of the school was a paltry 30 rupees a month! Not only that, he used a good part of the money he earned from his concerts for the school.

Vinayakrao named the school as a Mahavidyalaya after the wishes of his guru Vishnu Digambar. He saw his school as a place to teach youngsters not only to sing, but also the art and science of music. He saw it too as a place to groom performers and teachers of music who would carry on his own mission.

The school, which followed the broad vision of Vishnu Digambar, had some important distinguishing features:

* Its aim was the propagation of music. The hope was that some of its students at least would help in teaching and spreading music in different parts, while the rest would develop a keen ear for music.

* It paid special attention to the students' progress in music as well as developing their knowledge of music.

* It attached a great deal of importance to discipline in music, as well as in conduct and life.

* The Principal of the school led by precept and example. He practised what he preached and was a model for his staff and students.

* It kept the tuiton fee low as a matter of policy, in order to encourage boys and girls belonging to different strata of society to enrol as students.

The Gandharva Mahavidyalaya soon gained in popularity and even adults evinced interest in learning music. On their request, separate classes were held from 5 to 6 pm so that they could attend the music class after their return from work.

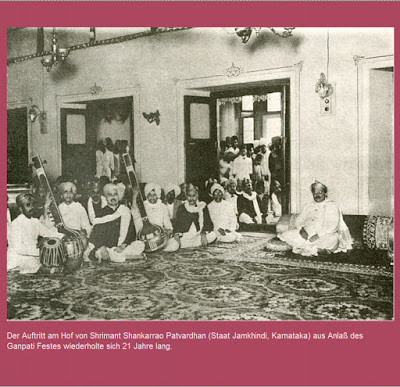

The smooth running of the institution was badly disrupted for a period of three or four months when plague struck Pune. The school had to be closed during that period. When it was eventually reopened, it faced a new kind of problem: the available space was inadequate to accomodate the swelling number of students. This was in 1934. At this juncture, Maharaja Sankarrao Patwardhan of Jamkhindi, a patron of the arts, came to the rescue. He leased a 12-room mansion of his to the school at a monthly rental of only 90 rupees.

The student strength had now gone up to 150 and classes were held morning, afternoon and night. Students were taught at four levels for different examinations: Pravesika, Madhyama, Visharad and Sangeet Kushal. Vinayakrao lived on the premises and devoted most of his time to the school, whether it was teaching, supervision or administration.

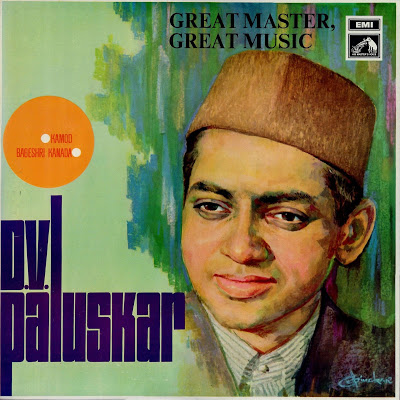

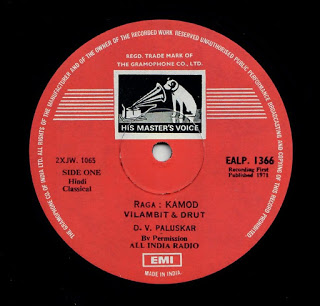

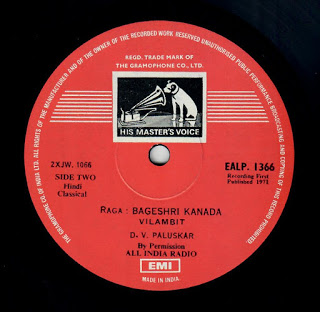

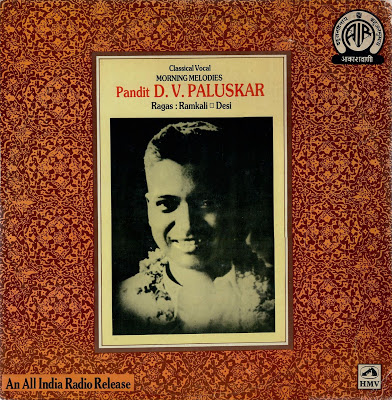

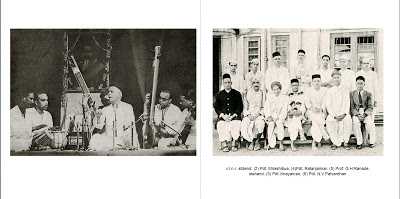

Patwardhan trained a very large number of students. There was of course his own son Narayanrao (b. 1925) who later became associated with the Akhil Bharatiya Gandharva Mahavidyalaya Mandal. A most illustrious musician who was taught by Patwardhan was Dattatreya Vishnu Paluskar, son of Vishnu Digambar. D.V. Paluskar was only 10 years of age when he lost his father. He was first sent to Narayanrao Vyas for training but the latter could not find sufficient time to teach the boy. Then Patwardhan took over the task, considering it his sacred responsibility and a duty owed to his late guru. The book Vandey Vinayakam, published by Pt. Vinayakrao Patwardhan Smarak Samiti, lists the names of as many as 91 disciples of Vinayakrao. Some of them were Vinaychandra Maudgalya, S.B. Deshpande, V.R. Athavale, Lakshmanrao Kelkar, Vishnu Ghag, V.D. Ghate, Janardhan Marathe, Mukundrao Gokhale, Rambhau Chandurkar, Sunanda Patnaik, Sakuntala Palasopkar, Leela Sardesai and Kamal Ketkar. Three others, Lila Limaye, Sita Mavinkurve and Indu Sohni were called the Three Nightingales at a music conference held by the Prayag Sangeet Samiti in Allahabad in 1934. A royal, Rajkumari Mangalraje Patwardhan of Miraj, studied under him for several years.

In 1942, Patwardhan handed over his school to the Bharatiya Sangeet Prasarak Mandal. He did so because he felt that it should not be dependent on one individual and that the Mandal, which was being run by a team of trustees, could better assure continuity. He did not, however, discontinue his association with the institution.

On 1 May 1952, Vinayakrao established the Vishnu Digambar Sangeet Mahavidyalaya in Pune in memory of his guru.

In keeping with his role as music missionary, Vinayakrao established another institution, the Vishnu Digambar Smarak Mandir, in Miraj on 25 February 1966. It was inaugurated by the then ruler of Miraj Srimant Narayanrao alias Tatyasaheb Mirajkar. The Smarak Mandir served as an effective platform for showcasing numerous musicians, and the death anniversary of Vishnu Digambar Paluskar was observed every year without fail. It is a standing testimony to the memory of Paluskar and his mission of propagating music.

Career as concert artist

Vinayakrao's career as a concert artist began even when he was a student.

In 1913, he sang at the wedding of the daughter of the Holkar of Indore and received the then princely sum of 500 rupees as well as a 'mahavastra'.

He had several opportunities to sing also at the sangeet sammelans or music conferences organised from time to time. The first one he attended was organised in the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya premises in March 1918, and it helped him to get an insight into the practical aspects of music first hand. He found that giving recitals, however brief, in the presence of stalwarts like Ichalkaranjikar, Bakhle, Vaze, A.M. Joshi and Rahmat Khan, was also a learning experience.

He presented a number of music concerts in Nagpur when he was Principal of the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya there.

He continued his pursuit of classical music even during his long innings with the Gandharva Natak Mandali. Bal Gandharva was very fond of him and respected him for his steadfastness to classical Hindustani music.

In March 1926 he was introduced to Mahatma Gandhi and sang two songs before the latter in Sabarmati.

Vinayakrao's first programme broadcast by All India Radio was on 15 August 1927.

The calendar entries continued like this, for all of 52 years. Altogether, he had a rich and varied experience, giving more than 1000 performances in various places and on various occasions.

His concert career took him abroad also. In 1954, he went to the U. S. S. R., Poland and Czechoslovakia as a member of a cultural delegation and, in 1956, to Nepal with a team of musicians.

Vinayakrao's gayaki was essentially that of the Gwalior gharana to which Paluskar belonged, but it was generally considered a subsidiary branch of it. He gave importance to the alapa in his music. He would develop his singing- boltaan, bolbant and taan- on the lines of the bandish.

Vinayakrao's deep respect for classical values was reflected in his music. He was faithful to traditional raga-s and was not interested in discovering new ones. He would usually sing raga-s like Asaveri, Bagesree, Bhoop, Darbari, Desi, Hameer, Jaunpuri, Jaijaiwanti, Suddha Sarang and Todi. Sometimes he would choose less frequently heard raga-s, like Anandi Kedar, Jayant Malhar, Malgunji and Ramdasi Malhar. He also learnt a few raga-s of Carnatic music.

Khayal, tarana and bhajan were his favourites; he shunned thumri, dadra and tappa. He had a forceful style in rendering tarana-s, with tongue-twisting syllables. He used expressions like 'dir-dir' and effortlessly pass from drut to anudrut. In 1954, when Vinayakrao went to the U.S.S.R. and sang before an august gathering which included the nation's leader, this aspect of tarana-singing aroused the curiosity of the Soviet leader. After the concert, the latter complimented Vinayakrao and then asked him whether he had kept some kind of device in his mouth!

Possessed of a powerful voice, Patwardhan had full mastery over laya, and speed did not deter him, Once, when some mischievous organisers of a concert put two master tabla players on the stage along with him in the hope they would trip him up, he took it in his stride and got through the concert without any discomfiture.

So confident of his own mastery of music was he that he would openly encourage his accompanists and express his appreciation of their performance freely. He would also give them sufficient opportunity to play, just as he gave chances to his accompanying disciples to sing.

According to Dr. Sumati Mutatkar, his music was a strange combination of discipline and freedom.

Patwardhan revelled in singing bhajan-s. Some of his favourite bhajan-s were Ab ke thek hamarey in Kafi, Raghukul reet sada in Jaunpuri, Mai Giridhar aagey nachoongi in Bahar and, of course, Jogi mat jaa in Bhairavi, which he sang to great effect. He would also sing popular numbers from natyasangeet when there were requests from members of the audience, as there were often.

One well-known critic averred that Patwardhan's bhajan-s lacked the correct style and sounded like orders to god. He likewise disliked Patwardhan's tarana-singing which he described as an exercise in the display of speed. But he seems to have been in a minority.

Even when performing, education was always on Vinayakrao's mind. For the benefit of the audience, he would announce the names of the raga-s before rendering them.

He had many other achievements as well to his credit.

He served for some time on the audition board of All India Radio.

As the Principal of the Vidyalaya in Nagpur and later as the head of the institutions he himself set up, he showed himself to be an able administrator. In between, in 1928, he demonstrated his administrative acumen and skills serving as the secretary of a three-day music conference. He did that again when, in 1934, he led a fund-raising programme organised by the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya to help the victims of the earthquake in Bihar.

He was an author as well. He wrote many text-books on music for use in his school

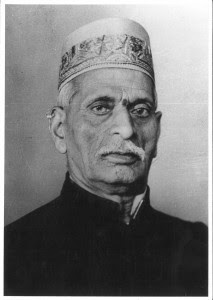

He received many honours, including Fellowship of the Sangeet Natak Akademi (1965) and the Padma Bhushan (1972).

Altogether, he had a long and illustrious career spanning more than half a century. Through all this, he remained true to the memory of his revered guru Vishnu Digambar Paluskar and modeled his life and career in keeping with his vision and teachings. Even during his years in the theatre, he defied all temptations and stayed true to the path he had chosen. A god-fearing man, he would recite the Gayatri mantra every day. He was uniformly courteous to everyone, great or humble. And he was an interesting conversationalist.

He died on 23 August 1975 in Pune. He was scheduled to sing a jugalbandi with Narayanrao Vyas that evening but it was not to be.