Tuesday, 22 October 2013

Thursday, 10 October 2013

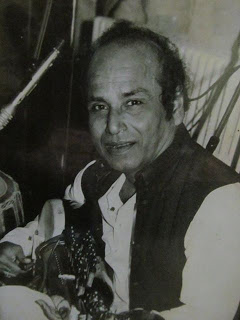

Ghulam Hussein Khan - Musique Classique Indienne - LP published in 1968 in France

Ustad Ghulam Hussein Khan belongs to a line of Bin and Sitar players, based in Indore and going back to the legendary Bande Ali Khan (1855-1922).

Side 1:

1. Dadra in Raga Pancham Se Gara

2. Raga Priti Hindoli

Side 2:

Raga Jhinjhoti

Ustad Ghulam Husain Khan was born in Indore in 1927. Since his father died

shortly after his birth, he took his musical training from his elder brother,

'Usman Khan. He began by playing the bin, but gradually realized that in the

changing musical climate of India the sitar held a more promising future, and he

eventually concentrated on the latter instrument in his lessons with his

brother. As a general rule when he was young, he mischievously neglected his

practice for typical childhood preoccupations (kite-flying, bicycle-riding, and

the like). Only after a program in which a cousin was highly praised for a fine

performance on the sitar--while Ghulam Husain, wearing (as he vividly remembers)

his customary short pants, was sent to fetch water for the guests did he feel a

motivation, born of pangs of humiliation and envy, to begin practicing in

earnest. With much riyaz and mahnat (practice and industriousness), he

progressed rapidly,and was appointed a Court Musician at the age of eighteen or

nineteen, shortly before Independence; after 1947 he accompanied his brother

'Usman to Bombay, where he quickly began to establish a reputation as an

outstanding sitarist. He remained in Bombay after 'Usman Khan moved to

Ahmedabad, and performed there very successfully until he was summoned to

Ahmedabad by 'Usman, who was returning to Indore at the invitation of the

Maharaja. Ghulam Husain was thus required to take over his elder brother's

teaching responsibilities, and he reluctantly left Bombay for

Ahmedabad.

He was clearly the best sitarist in that city, and he soon

developed a considerable, if geographically limited, reputation. He was able to

discontinue the classes he had taken over from his brother, and to earn a

comfortable income from radio performance, local programs (both public and

private), and the private instruction (in "tuitions") of a few wealthy devotees

of Hindustani music. While not performing often in other parts of India outside

Ahmedabad, he did make a European and American concert tour, sponsored by the

Pan Orient Arts Foundation of Boston, in 1968, followed by a second European

tour in 1973. His reputation in India has now spread beyond Ahmedabad, and he

has performed on one long-playing record released in India and three other

records issued abroad.

To a great degree, Ghulam Husain Khan has adhered

to the traditional principles of ustadi which have already been discussed: riyaz

(practice) and mahnat (industriousness); the development of a distinctive style,

arising out of traditional elements, in what he calls binkar baj (playing the

sitar in the style of a binkar); the maintenance of mithas (musical sweetness)

so treasured by 'Usman Khan as the hallmark of the instrumental style of Bande

'Ali Khan; a sense of dedicated khidmat (service) to the gharana; and a basic

respect for sadagi (simplicity) in style of life. Moreover, his sense of the

traditional instructional roles of the ustad is highly developed; he has not

participated in the establishment of any music classes, as have many of his

contemporaries, but remains dedicated to the principle of intensive individual

instruction and has limited the number of his formally bound shagirds

(disciples) to a few individuals who have clearly demonstrated their dedication

and seriousness.

While he has been creative in developing his own style

of binkar baj and in developing, after several years' effort, a new rag

(Priti-Hindoli)l it is rather in the larger social realm beyond pure music that

Ghulam Husain Khan has expanded his role as an ustad. He has, one might say,

become his own patron, and something of an entrepreneur, partly out of economic

necessity, but also partly out of a sense of khidmat to music and to the

gharana. In one sense he has developed a philosophy of how to live the "artist's

life"; in another he has defined for himself a role as a visibly productive and

responsible citizen. In short, Ghulam Husain Khan has become the most

accomplished musician of his generation in his immediate family, and the most

renowned as an ustad. A discussion of the various aspects of his life--both

musical and extra-musical will be of assistance in understanding the reasons for

his renown. extra-musical

Ghulam Husain Khan has a strong sense of the

importance of riyaz and mahnat for a musician, and he laments in a published

interview that he, like other contemporary musicians, does not have as much time

for practice as he would like: "Without patronage and respect, the musician

cannot devote the whole of this time and self to the music. In the old

days--even as recently as thirty years ago--it was not the same. His attitude

toward practice, however, is refreshingly realistic, partaking hardly at all of

the usual pious claims and pronouncements. While acknowledging that intense

practice was essential in the formative stages of his career, he recognizes the

equal importance of other elements as well:

Patience, obedience, industry,

and intelligence are the qualities necessary to a good musician. Through

learning the ragas by heart the power to play them comes. One becomes almost

hypnotized by the discipline of practice, and this reveals the growth of the

inner strength necessary for music.

In the development of his sitar style,

Ghulam Husain ,as combined the bIn style learned from his elder brother with

traditional elements of sitar performance in what he feels is a somewhat novel

approach to sitar playing--bInkar baj --thoroughly grounded in precedent in each

of the two individual instrumental styles. As already mentioned, 'Usman Khan

identifies his bIn style, derived from that of Bande 'Ali Khan, as being

distinguished by the introduction of a khaval sensibility and technique into the

traditionally dhrupad-oriented style of the bin. Thus Ghulam Husain feels his

music to have a strongly vocal quality for which he uses the phrase gayaki ang

(used as well by some other musicians, notably Ustad Vilayat Khan) ; and he adds

the further qualification that his performance includes elements of thumrI and

dadra (forms of light classical music) as well. In the specific flavor of his

playing, he, like 'Usman Khan, has tried to maintain the quality of mithas

(musical sweetness) through the use of srutitI (microtonal variation), murki (a

delicate quaver at the end of a note before a descent), and zamzama (a

particular type of occasional tremolo.) His performances are enriched by his

knowledge of a large number of old gats ( compositions), including many rare

double gats (compositions, in the Raza KhanI or fast pattern, having two parts

and lasting two-full-cycles of tIntal, the rhythmic cycle which has sixteen

beats) from past ustads in the gharana.

Ghulam Husain Khan's sense of

khidmat (service) to the gharana is clear. He has remained more concerned than

his brothers about the fate of his musical tradition, and a conversation with

him often reveals some hope or anxiety prompted by this concern. (This aspect of

his ustadi will be treated in an elaboration of his educational philosophy, and

in the section on the gharana itself). On the personal level, Ghulam Husain sent

his firstborn son, Afzal Husain, to live with and be raised by 'Usman Khan, Who

had no son of his own (it was only from a third marriage years later that 'Usman

was to have two sons). In fact, out of a general deference toward and sympathy

for his older brother (who very much wanted children of his own.), Ghulam Husain

has had all his own children call Usman Khan Babba (roughly equivalent to the

English papa), while he himself is addressed as bha'i miyan (respected brother).

He also has a clear sense of social khidmat--to be discussed presently--as a

citizen of his community in contemporary India.

While not an

ostentatiously pious man (he has a wry sense of humor and an engaging personal

warmth) Ghulam Husain Khan does observe certain principles of sadagi. On almost

all occasions he wears a plain white kurta and pa'ijama (loose, flowing shirt

and pajama-like trousers) made of simple cotton, neatly pressed. He takes very

seriously attendance of ceremonies at the tombs of saints (the roza of Shah

'AIam in Ahmedabad is a favorite visiting place for him), and he prays regularly

before his performances. When he was congratulated by a few close friends after

a particularly moving and successful debut performance in the United States, he

shook his head with stark and genuine humility and said, "maih ne kuch nahin

kiya khud ne sab kuch kiya" ("I did nothing--it was all done by God"); one had

the distinct impression that he believed utterly that the music had flowed

through him from a divine source.

But it is in his dedication to teaching

that Ghulam Husain Khan has shown some of the most dominant aspects of his

ustadI. The importance of posterity in the maintenance of a gharana is evident

to him, and for this reason, with a sense of khidmat to the gharana, he has

taken the process of teaching very seriously. A distinction has already been

made between an ustad's attitude toward uncommitted students and serious

disciples. Casual students he treats casually, but his few shagirds (he has

taken perhaps eight such disciples, exclusive of his sons, in thirty years of

teaching) are the recipients of his utmost dedication. In the interview from

which he has previously been quoted, he describes his view of the relationship

between ustad and shagird:

The ustad gives his pupil the maximum

personal attention possible. He spends from five to ten hours a day with him,

until the disciple understands the mind as well as the movements of the teacher.

The teaching of music is the creation of a complete understanding between the

two.

Sometimes the ustad disciplines his pupil to be certain that the

disciple is serious. An American boy came to me several years ago, wanting to

study the sitar. I was not sure of him so I called him at midnight, at five in

the morning, in rain and sun, to test his discipline and patience. Finally I was

satisfied and took him. Now he is like a son to me. Ghulam Husain Khan takes his

obligations to his shagirds not only as a musical relationship, but as a

spiritual and very personal one as well. Certain features of his preceptive

philosophy are similar to those of the Sufl tariqa (path), in which the

relationship between shaikh and murid often parallels that of ustad and shagird.

The aspect or-trial and testing by the ustad shaikh has already been mentioned,

as has the aspect of suhbat(literally, company, but in Sufism, spiritual

conversation), in which ustad and shagird become well acquainted through

extensive conversations and long periods of time spent in each other's company.

Writing of the symbolic use of clothing in Sufism, Schimmel (1975:102) has

observed that "by donning a garment that has been worn, or even touched, by the

blessed hands of a master, the disciple acquires some of the baraka, the

mystico-magical power of the sheikh." In numerous instances Ghulam Husain has

followed this particular symbolism as well by presenting his male shagirds with

both new clothes, particularly kurtas, and clothes which he himself has worn.

This last custom in particular is typical of his generosity to his most trusted

disciples.

In a more public context, as mentioned earlier, Ghulam Husain

has become something of a musical entrepreneur. He has realized that with the

loss of courtly patronage, it is difficult for a musician to survive with the

degree of passivity that often results from an adequate monthly stipend; he has

therefore developed in himself, quite against his ultimately shy and

self-effacing nature, certain entrepreneurial capabilities that have borne

significant results. In 1962, for example, he gained publicity, prestige, and

merit as a citizen by arranging his own benefit program for the national defense

fund instituted during the border dispute with China. He personally canvassed

the city of Ahmedabad to sell tickets to the wealthier residents of the city,

and when he was refused entry because of his modest appearance, he would gain

audience with his patrons-to-be after passing with

much good humor through

the servants' entrance. "I am not a proud man," he would say, laughing; "this is

the artist's life"--and then, "you must buy tickets to my program. It will be a

good program, in a good cause." He sent a very substantial sum received from the

concert to the fund, and is still remembered for this in Ahmedabad.

Feeling, as many traditional ustads would not, this sense of public

interest and duty, Ghulam Husain Khan has thus become something of a patron

himself--dispensing, if not money, at least moral and tactical support. During

his early days in Ahmedabad, when there was little musical activity in what was

primarily the business-oriented center of an expanding textile industry, he was

cofounder of "Alap," a music circle organized to bring visiting artists, to the

city and thereby enrich its cultural life. He has also participated

conscientiously in anniversary programs honoring the memory of two of the major

figures in the modernization of Indian music education, V.D. Paluskar and V.N.

Bhatkande; in this connection he received a special reception and award,

presented by the Finance Minister of India, from the Gandharva Mahavidyalaya

Mandal. a well-known modern music school.

This last point suggests not

so much that Ghulam Husain Khan participates in current trends in the

modernization of classical music, as that he wants to acknowledge the fact that

such trends exist. To remain informed on various musical developments, he

subscribes to at least one musicological journal published in Hindi. In many

respects, his reading of this journal has the same motivation as his reading of

newspapers: diversion, with an intelligent interest in the events--musical or

otherwise of the day. (While maintaining that very little of practical value can

be learned from books on music, he does occasionally consult a

nineteenth-century Urdu treatise on music, Sarmaya-e-'israt, (sadiq 'Ali Khan

1895) particularly regarding aspects of instrumental maintenance and repairs in

which he takes a keen interest. His apparent trust of this book is possibly due

to the fact that the author, Sadiq 'Ali Khan, has the same name as the father of

Bande 'Ali Khan, the founder of Ghulam Husain's gharana, and may well be the

same person.

In most respects, Ghulam Husain Khan approaches his public

role as an ustad with a particular savor and witty nonchalance that

characterizes what he calls "artist's life"--the life of an individual seen, as

a Muslim musician, as being somewhat on the periphery of traditional Indian

society no matter what the degree of art. When he lived in Bombay, Ghulam Husain

moved in a polyglot community of painters, poets, 'and other musicians: he lived

for a time in a flat on Malabar Hill where the famous Urdu poet Faiz Ahmad Faiz

had recently lived, and which had a history of tenants arrested for offenses

ranging from gambling to political terrorism. He still remembers those days and

those individuals with pleasure. Yet, coming to Ahmedabad on his brother's

instruction, he left the Bohemian life when he realized that it would ultimately

be detrimental to his stature as a musician, and to the stature of the gharana,

in the public eye; instead of squandering a growing income, he began to invest

in the future through the cultivation of a distinct image and selective

acquisition of property.

Traditionally, Muslim musicians who, before

independence, were associated with the courts of princely states, have tended in

many respects to imitate the manners and pursuits of their patrons, the Hindu

maharajas and the Muslim navabs: hunting, Epicurean dining, a fondness for

elegant clothes, and a great pleasure in the adventure of travel. Ghulam Husain

is very much of a gourmand, and for some years met regularly with a group of

fiends, known as the Murghr (chicken) Club, who would take turns hosting meals

In which no effort, and sometimes ( depending on the means of the host) no

expense, was spared. During his four-month stay at the University of Chicago,

Ghulam Husain cooked sumptuously for his numerous guests, and ate frequently in

the city's different ethnic restaurants. Even today, he is fond of going, at

five o'clock in the morning, for breakfast to the narrow, smoky, congested

street in Ahmedabad known as bhathiyara gali, where bara handi ("twelve

pots"--viscid and spice-ridden curries of all edible portions of the goat:

brain, tounge, heart, liver, tripe, lung, trotters, and all the usual cuts) is

served by the light of kerosene lamps to a motley of dozing Muslim laborers and

idlers, and the occasional ustad. Traveling, too, is diverting for Ghulam

Husain, who can be an enthusiastic tourist, particularly when he is abroad,

unlike some Indian musicians who have difficulty in foreign cultures. As already

mentioned, his ordinary dress is simple, though conspicuously long and flowing

in its cut, typical of ustads; his taste for clothes worn in performance--still

a courtly occasion for him--tend toward pale but expensive raw-silk kurtas and

elegantly embroidered Kashmiri woolen shawls, for he believes that if an ustad

looks confident and successful, he will more likely be taken as such.

In

his own words, his dress is "a question of prestige" (prestij ka saval hai) , as

are his watch--with its spectacular metallic blue face--and his automobile. His

first automobile, purchased with painstakingly gathered funds in 1964, was most

of the time under repair; but when it was running, it became famous in Ahmedabad

as the lal pari (the red fairy). The vehicle bears description. Ancient and

British--perhaps a vintage Austin or Morris-- it was a quaint, stylish

two-seater convertible, painted a dark but highly visible crimson. Ghulam Husain

always dove the car to tuitions, and often took his children ( three sons, two

daughters) or friends for a conspicuous tour of the city. Ramshackle though the

automobile was, the fact that it was driven by a musician was not lost upon

Ghulam Husain' s friends and the public at large. Few professional musicians in

India can afford automobiles, and it is probable that in 1964 no other musician

in the state of Gujarat had a car of his own. Though he enjoyed. the notoriety

of the lal pari for a time, Ghulam Husain sold the car when its mechanical

difficulties became too troublesome, and he purchased a somewhat newer

Indian-manufactured Fiat which, though still needing frequent repairs, was

certainly more practical and dignified than its whimsical predecessor. But the

point had been carefully made: even people who did not attend his concert" knew

that Ghulam Husain Khan was a visibly successful Ustad

This is not to

say that Ghulam Husain makes ostentation a way of life. His modest flat in

Ahmedabad consists of two rooms and a partitioned verandah; it is located behind

a petrol station in the old part of the city, in a large fifty-year-old compound

that includes ~ miscellany of families of extremely diverse religious, regional,

and even national backgrounds. Nor has his return from his foreign tours

significantly changed his style of life. It seems more a function of the passage

of time than of self-conscious change that his wife no longer keeps rigid parda

(the traditional Islamic veiling of women); that he recently obtained a

telephone to facilitate communication with his students, disciples, and friends;

that he occasionally wears suits (as he did be: his tours) to social occasions;

and that he now eats at small metal table with one or two of his children

(though when guests come to his home, tea and dinner are still served on the

traditional dastarkhwan spread on the floor.) He remains in touch with most of

his close friends of fifteen years ago, though he has made many new friends as

well. In all these respects, his life as an ustad has seen not so much a radical

alteration as an expansion and enrichment of the traditional roles.

Sunday, 6 October 2013

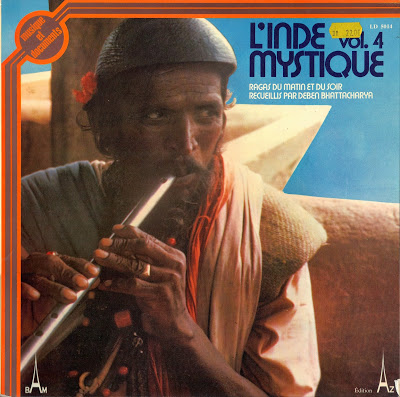

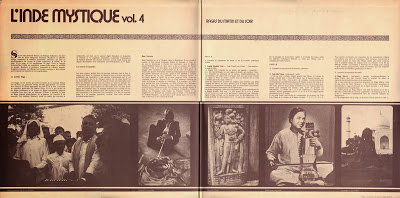

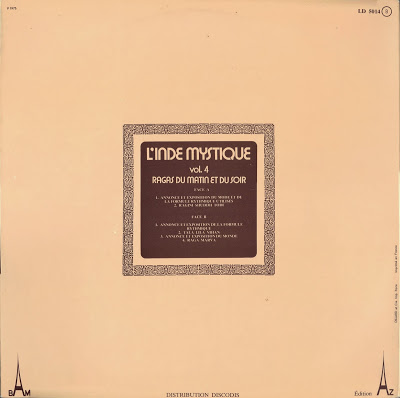

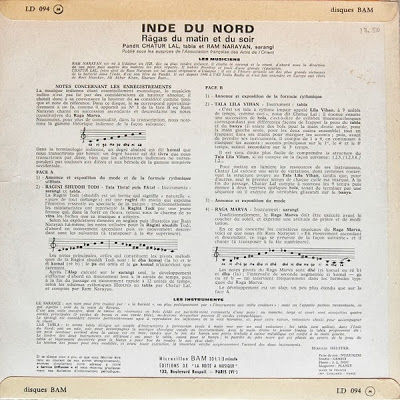

Ram Narayan & Chatur Lal - Ragas du Matin et du Soir - Re-edition of a LP published originally in France in 1964

This is a 1976 re-edition of a 10" record published by the same label originally in 1964. See below the original covers (taken from Discogs). The 1976 edition has less surface noise.

Covers of the original 1964 edition:

Thursday, 3 October 2013

Munir Khan - Indian Classical Music - LP published in the Netherlands in 1974

The first LP by the great Sarangi master. See also our earlier post here.

Side 1:

Raga Desi

Side 2:

Raga Purya Dhanashri

Thursday, 26 September 2013

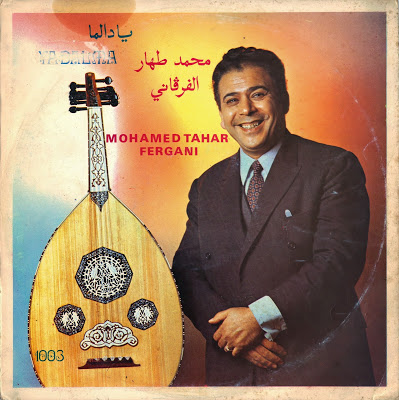

Mohamed Tahar Fergani - Ya Dalma - LP published in Algeria

LP probably published in the 1960s or 1970s. It contains one of his most famous songs, Ya Dalma (the unjust), in an extended version.

See our earlier posts:

About the artist, see also: http://musique.arabe.over-blog.com/article-19746413.html

Wednesday, 11 September 2013

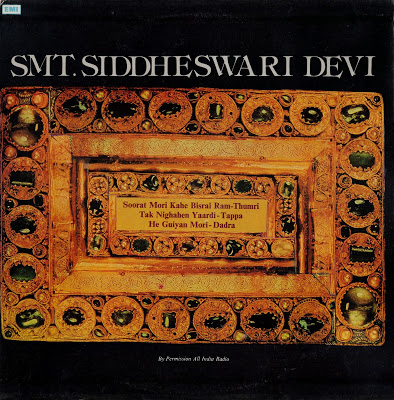

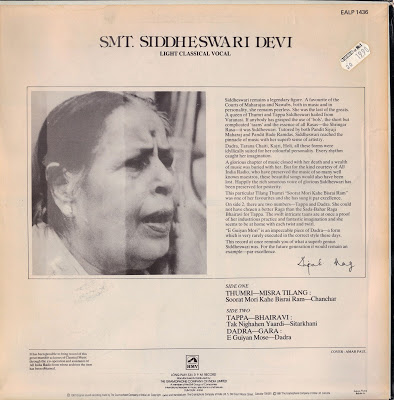

Siddheswari Devi (1908-1976) - Light Classical Vocal - From the archives of All India Radio - LP published in India in 1985

Side 1:

Thumri - Misra Tilang

Side 2:

1. Tappa - Bhairavi

2. Dadra - Gara

Smt. Siddheswari Devi

With the passing away of Siddheswari Devi on March 18 1977, the last of the four great pillars of Hindustani light classical music is gone. First went Begum Akhtar in 1974 at the age of 60, and then her older contemporaries, Rasoolan Bai, Badi Moti Bai and Siddheswari Devi. All four of them were inheritors of great traditions of music from a glorious era of the past when music dominated the lives of musicians from childhood to death. They were musical `stars' who shone brilliantly in the courtly era; but when the `darbari' era ended they did not hesitate to step out into the glare of public acclaim.

Thumris were once sung with abhinaya. When classicists began to frown down on this type of music with abhinaya, the singers took to the Bol-Banav-ki Thumri in which the emotional contents of songs are effectively brought out through vocal expressiveness only, that is, beauty of notes, voice modulations swara-combinations, and a specially emotion-charged style of singing. Bhaiya Ganpatrao, Moizuddin, and Shyamlal Khatri were some of the trail-blazers who gave this modern orientation to Thumri. Among those who have kept up these traditions till now in full glory, the outstanding names of this century have been Siddheswari Devi, Rasoolan Bai, Badi Moti Bai, Begum Akhtar, Mahadev Prasad Misra, and Girija Devi. Girija Devi is far younger than the others, and is of a different generation.

Born into a famous musical family in Varanasi in 1903, Siddheswari traced her musical lineage to her maternal grandmother Maina Devi, a reputed singer of Kashi of nearly a century ago. She was the inheritor of great musical traditions from a family which produced several famous singers like Maina Devi, Vidyadhari Devi, Rajeswari Devi and Kamaleswari Devi. As Siddheswari lost her mother when she was barely 18 months old, she was brought up by her maternal aunt, Rajeswari, who was a famed disciple of Maina Devi, Mithailal, and of the great Moizuddin himself. Brought up in this musical atmosphere, Siddheswari absorbed a great deal of the art right from her infancy. Her childhood was an unhappy one as she lost her father also very soon. About this period of her life, she once said : "We did not have luxuries like the gramophone. But our neighbours had one. I used to go to them to listen to the records of popular singers like Janaki Bai, Gauharbai and several others. How their music used to captivate me!".

Noticing the talent and eagerness of the young girl, Siyaji Maharaj began to teach her. Siyaji's father Shyamacharan Misra, and uncle Ramcharan Misra had been good musicians. About her guru, Siddheswari used to say : "No one could possibly get a more generous and affectionate guru. Having no children of his own, he treated me like his own daughter. He taught me all the basic ragas and a large number of Khayals, Tappas, and Taranas. He taught me with all his heart, and I practised my music with intense concentration and devotion. Nowadays, alas! the students are all in a hurry to acquire a diploma or a degree; they have no lagan."

After the death of Siyaji Maharaj, she learnt for a while from Ustads Rajab Ali Khan of Dewas, and Inayat Khan of Lahore. However, her greatest guru, the one to whom she attributes most of her musical training was none other than Bade Ramdasji of Varanasi. Her face glowed with pride and veneration whenever she spoke about this generous guru who taught the eager disciple magnanimously. Nostalgically recalling those times of close guru-shishya bonds, Siddheswari once remarked to me : "The age of such great and generous gurus seems to have gone. No longer does one come across the really devoted type of pupils either. Today they are all in such a hurry----"

Later on in life, when she joined the Bharatiya Kala Kendra in Delhi as a professor, she earned the reputation for being a sincere and conscientious teacher. When I mentioned this to her, she simply remarked : "Why not, Beti? Let something of my treasures remain with others after l am gone".

Siddheswari made her unforgettable debut at a Calcutta conference many many decades ago. Young Siddheswari's name was billed along with those of many of the veterans of the time, such as Pt. Omkarnath Thakur, Pt. Dilip Chandra Vedi, Ustad Faiyaz Khan and others. Her khayals in Malhar and Suha-Sughrai, and her thumris, elicited high praise and medals galore from Pt. Omkarnathji and Ustad Faiyaz Khan. Another glorious performance of her's was in the All India. Music Conference in Bombay in which Ustads Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Faiyaz Khan also were to sing. Siddheswari concluded her superb recital with such an intensely emotional rendering of the Bhairavi-Thumri (Kaahe Ko daari re gulal Brajlal Kanhayi) that the Aftab-e-Mausiqui refused to sing after her! He said to her : "After such music there is no room for any more. After Gauhar Malika, the crown of the Thumri rests on your head". Such was the grand magnanimity of the musical giants of the past!

After her first concert appearance at the age of 18, she began to receive invitations for performances in Rampur, Jodhpur, Lahore, Mysore and various other states which used to patronise classical music during that time. In the next 4 or 5 decades, she sang in many royal durbars, music conferences national programmes, radio concerts and so on until she became "an institution by herself in view of her enormous repertory and heritage of a rich musical tradition." In recognition of her valuable contributions to the enrichment and perpetuation of the Banaras (Poorab) ang of light classical music, Siddheswari was honoured with the Presidential Award in 1966, the Padmasri in 1967 the D. Litt from Rabindra Bharati University, Calcutta, and the title of "Desikottama" from the Viswa Bharati University. When we felicitated her on the Award, her humble and philosophical reply was : "It's all very well; but I shall continue to deserve these, only as long as I can go on singing well enough to please you all". In spite of all the fame that she earned, she remained simple, unassuming and homely till the end. Among contemporary musicians, Kesarbai Kerkar and M.S. Subbalakshmi were the artistes she admired most.

Few musicians in recent times had such a vast repertoire as Siddheswari had. Her rich storehouse included a large number of Khayals, Thumris, Dadras, Tappas, Kajaris, Chaitis and Bhajans. "A feeling heart, a fecund mind, and an expressive voice" are the prime requisites for a good light classical singer. Even when her voice had become "temperamental and thick" in old age, she could make up for it by a rare emotional fervour, and she could hold her audiences by her mood of intense absorption and her ability to bring out the emotional contents of the romantic or devotional themes. Siddheswari's music brought out all the salient features of the Banaras style, such as simple charm, intensity of feeling, and effective expression of emotions through sheer purity of notes, "meends" and voice modulations. She said to me once : "Although my thumri is fully of the Banaras ang, I incorporate elements of the Khayal into it. You may say that my thumri- singing is Khayal angapradhan". She added spice and charm by sprinkling short, swift tappa-like taans and trills. In her early days, she was deeply impressed by the singing of Gauharjan, Zohrabai, and Malikajan. As a member of cultural delegations, Siddheswari gave recitals in Rome, Kabul, and Kathmandu.

Siddheswari cherished not only the songs galore that she had learnt from her revered guru Bade Ramdasji, but also the lofty principles that he impressed on his disciples. He used to advise her: "Music is the medium for pleasing and attaining God. You should never feel proud of any success. Always remain humble. The day your tears flow during your sangeetsadhana, your music will have attained mellowness and maturity".

No wonder she always believed that both "Siddhi" and "Ishwar" can be attained through devoted sangeet-sadhana. Her deeply religious temperament had a great impact on her singing. In the last years of her life, the Pukaars in her Thumris and Bhajans were like cries from an anguished devotee's heart. With eyes closed, mind absorbed, and left hand cupping her left ear (to receive the full drone of the Tanpura), she used to pour her heart out through her music. Siddheswari remained a most warm-hearted, simple, and loveable person, "an extraordinary amalgam" of innocence, courage, humour, generosity, youthful zest for life, and a rare dignity. Her life was, by no means, a happy or smooth one. She had an unhappy childhood and "an emotionally tumultuous" youth, and she had to undergo many bitter experiences in life. But all of these seem to have added to her natural dignity, strength and wisdom. One of her admirers described her as "a vast reservoir of warmth, an unfailing fountainhead of inspiration, a manifestation of humanity at its most compelling and earthy.... and yet a being full of sparks and sudden vertical ascents to the mystic regions where inspiration has its divine origins". She did not have the facilities to devote herself to sadhana; living like a recluse. She practised her music all the time, while she was cooking, washing clothes, or doing any of the ordinary household chores. Music was her very Iife.

The death of Siddheswari Devi has left a big void in the world of light classical music. Shanta Devi, her elder daughter whom she had trained up to follow her footsteps has remained in obscurity owing to poor health. Surprisingly, it is her younger daughter Savita Devi who has zoomed into the limelight as a delightful and popular singer, and it is Savita who shows every sign of taking her illustrious mother's place. Versatile and attractive Savita is not only a graduate (an M.A, and Sangeetalankar) and a good Sitariya, but she has also shaped into a confident and popular vocalist with a wide repertoire of Khayals, and light classical varieties. Gifted with an appealing, melodious voice covering 3 octaves or more, she has undergone years of training in khayals under Pt. Moni Prasad of the Kirana gharana. She has a natural flair for the light classical varieties in which she was extensively trained by her mother whom she used to accompany as a supporting singer in many concerts. While working as Head of the Department of Music in Daulatram College (University of Delhi), she is continuing her own music riyaz tirelessly.

Many years before her death, Siddheswari had once told me : "My greatest ambition is to die while singing a perfect taan. I feel closest to God when I am lost in my music." Begum Akhtar also had expressed an almost identical wish which was fulfilled because she died in the peak of her glory, giving a memorable performance before the dropping of the final curtain.

But Siddheswari who lived till her seventies, had no such luck. She had been helplessly bed-ridden for many months prior to the sad end. In a TV interview prior to her last illness, she had confessed with dignity:- "There was a time when I used to sing for the public. Now I sing to please my God. My soul craves to go back to its original abode".

Malini Menon, one of Siddheswari's pet-pupils who had become more like a daughter to her, writes:- "Maa remained a student all her life. . .She had a child-like thirst for knowledge and she was ever so generous as she could not bear to see anybody in want... Maa was turbulent as the waves, and yet calm like the distant sea. She was at peace with herself and had prepared for the journey of the soul to eternity. When the moment came, she accepted it with grace."

Siddheswari Devi's last brilliant recital was in the Radio Sangeet Sammelan (a couple of years before her end) in which she sang with a bubbling, youthful zest, accompanied on the Sarangi by Pt. Gopal Misra (who is no more), and on the Tabla by Ramji Misra. Eyes twinkling, the solitary diamond in her big nose ring flashing points of light, a warm smile on her paan-reddened lips, Maa's homely figure emerges in one's memory. But as soon as she sat on the stage for a recital, one realised that she belonged to an entirely different world, and that her life had known "no horizons other than music". As I recall that last inspiring recital of hers in the Radio Sangeet Sammelan, memories of several other great past concerts of this music-devotee come to my mind, and her plaintive Jogiya echoes in my memory:"O Jogi ! Constantly uttering the name of Rama, you have become one with Him, leaving your little hut so empty---".

Posted on RMIC by Rajan Parrikar as part of Great Masters Series.

From: "Great Masters of Hindustani Music" by Susheela Misra.

From: "Great Masters of Hindustani Music" by Susheela Misra.

Wednesday, 4 September 2013

Jotin Bhattacharya - Sarod - LP published in 1974 in India

Side 1:

Raga Marwa

Side 2:

Raga Sampurna Kanada

Jotin Bhattacharya

"Renowned Sarod player and direct disciple of Baba Allaudin

Khan

Biografie:

Pt. Jotin Bhattacharya was born in Varanasi on 1st Jan, 1926. His quest for music and Philosophy lead him to seek two greatest teachers of all time in their respective fields, one being Dr. Radhakrishnan and the other being Ustaad Allaudin Khan (Mahiyar). After completing his Masters in Philosophy from BHU, his unquenched thirst for Indian Classical Music, ultimately lead him to Mahiyar. He spent almost 16 years learning from Baba.

The enormous treasure that he accumulated from Baba, was evident during all his public performances. There were series of concerts all over India and all music pundits and critics acknowledged that indeed the legacy of Baba has been truly preserved by this talented musician. His first album brought out by HMV in 1972 (more correct year: 1974) was one of the rarest gems in Indian Classical Music comprising of Raag Marwah and a self composed Raaga called “Sampurna Kanhara”.

He created more than 40 Ragas some of the popular ones listed here: Mouni, Sampurna Kanhra, Amarawati, Mateswari, Sardeswari, Mohini, Chandra Mouli, Lachmi, Biyogini ...

Panditji’s constant dedication towards his Master prompted him to write some memorable books which are greatly appreciated not only by music connoisseurs but also by musicologists all over the world. His first published book on his Guru “Ustaad Allaudin Khan and his Music”, was an authorized biography of Baba Allaudin Khan. This was followed by 2 books which were published in Bengali and Hindi named “Allaudin Khan O aamara” i.e “Allaudin Khan and Us”. These two books were also greatly appreciated by Music connoisseurs."

Biografie:

Pt. Jotin Bhattacharya was born in Varanasi on 1st Jan, 1926. His quest for music and Philosophy lead him to seek two greatest teachers of all time in their respective fields, one being Dr. Radhakrishnan and the other being Ustaad Allaudin Khan (Mahiyar). After completing his Masters in Philosophy from BHU, his unquenched thirst for Indian Classical Music, ultimately lead him to Mahiyar. He spent almost 16 years learning from Baba.

The enormous treasure that he accumulated from Baba, was evident during all his public performances. There were series of concerts all over India and all music pundits and critics acknowledged that indeed the legacy of Baba has been truly preserved by this talented musician. His first album brought out by HMV in 1972 (more correct year: 1974) was one of the rarest gems in Indian Classical Music comprising of Raag Marwah and a self composed Raaga called “Sampurna Kanhara”.

He created more than 40 Ragas some of the popular ones listed here: Mouni, Sampurna Kanhra, Amarawati, Mateswari, Sardeswari, Mohini, Chandra Mouli, Lachmi, Biyogini ...

Panditji’s constant dedication towards his Master prompted him to write some memorable books which are greatly appreciated not only by music connoisseurs but also by musicologists all over the world. His first published book on his Guru “Ustaad Allaudin Khan and his Music”, was an authorized biography of Baba Allaudin Khan. This was followed by 2 books which were published in Bengali and Hindi named “Allaudin Khan O aamara” i.e “Allaudin Khan and Us”. These two books were also greatly appreciated by Music connoisseurs."

Sunday, 25 August 2013

Folk Music from Neyshaboor (Nishapur), Khorasan, Iran - Cassette published in Iran end of 1980s or beginning of 1990s

Chaharomin Djashnvareh Mousiqi Fajr

(4. Fajr Music Festival)

Neyshaboor - Mahali (regional or folk music from Neyshaboor or Nishapur)

Beautiful recordings of regional or local music (Mahali) from Neyshaboor in northeastern Khorasan. We had already posted a number of recordings from Khorasan before, one from northern and two from eastern Khorasan. American edition of a cassette originally published in Iran.

About Nishapur see: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nishapur

Monday, 19 August 2013

Khansahib Abdul Karim Khan (1872-1937) - LP published in India in 1966

This LP is a collection of some of the 78rpm records by one of the greatest and most influential singers of last century. See below for his biography.

Ustad Abdul Karim Khan

by Smt. Susheela Misra(From: "Great Masters of Hindustani Music" by Smt. Susheela Misra.)

In the early decades of this century, Khan Saheb Abdul Karim Khan dominated the world of Hindustani music for well over a generation, and he was a trend setter in this world in more than one sense. He created a new style or gharaana and gave an elan to the history of Hindustani music. He has been acclaimed as the "maestro who conceived, evolved, and popularised the Kirana gharana", and in fact, he changed the entire mood of Khayal and Thumri-singing. Dr. S.N. Ratanjankar wrote to me once about him: "In the late Ustad Abdul Karim Khan Saheb's sweet, tender, and tuneful voice, the Hindustani melodies appeared in a role and mood quite different from those in which they presented themselves in other voices...It was like a walk in a cool, moon-lit garden of sweet-smelling flowers that one felt when listening to the perfectly tuneful, and dreamy cadences of Khan Saheb's music One was lifted up into a dream land. The dream haunted the mind long after the music had ceased. The Khan Saheb never sang a raga, but was in holy communion with it. It was the very divine world, as it were, which made you forget the opposites, and led you to the perfect unity with the Supreme spirit".

Those who have been able to hear the Ustad's music only through his gramophone records, become aware of many shortcomings in his style such as the nasal twang in the voice produced through "a deliberately constricted throat", lack of bol-alaaps, bol-tans, rhythmic play, variety and grandeur. But, his contemporaries who had the good fortune to hear him in person were completely hypnotised by the sweetness of his music and his aesthetic emotion-filled rendering of ragas. Late Prof. D.P. Mukherji who was a reputed music connoisseur, wrote: "Abdul Karim Khan would invite us to enter into the sanctum of music where he was the high priest. He was not an orthodox singer. He would not even sing a composition through. His asthayi was not always true to form. He would make unexpected permutations and combinations. . . . . , But who cared when Abdul Karim Khan was on the dais ! This unorthodox man was a genius. ...Some of the finest exponents of Khayal today are either his pupils or his pupil`s pupils. "

His shishya-parampura includes a long array of celebrities such as Sawai Gandharva, Baharebuwa, Sureshbabu Mane, Balakrishnabuwa Kapileswari, Dasarathbuwa Muley, Roshanara Begum; Hirabai Barodekar and many others who in their turn, have groomed another generation of reputed singers like Bhimsen Joshi, Feroz Dastur,Gangubai Hangal, Manik Verma, Saraswati Rane, Prabha Atre and others.

Abdul Karim Khan was born in 1872 in Kirana near Kurukshetra in the Punjab. Subsequently the style or Gharana that he evolved was named after his birth place, Kiraana. In his perceptive book, "Indian Musical Traditions", Sri Vamanrao Deshpande rightly says that "each gharana has its origin in the distinctive quality of the voice of its founder and it is this quality which broadly determines his style." To this I would also add that the temperament of the founder also plays a considerable role in moulding the style of the gharana.

Abdul Karim Khan was perhaps the first North Indian musician to study Karnatic ragas and incorporate several of them into Hindustani music. His records of songs in "Kharaharapriya", "Saaweri", "Hamsadhwani", "Abhogi" etc. as well as his style of sargam-singing are proofs of his great admiration and love for Karnatic music. Perhaps no single classical musician in those days did so much for the promotion of mutual understanding between Hindustani and Karnatic music as the late Khan Saheb did. The greatest quality of his music was "emotion par excellence", and that was the reason why his classical music was able to move audiences everywhere, whether in the North or South of India. I know of many young men and women in South India who took to Hindustani music, charmed by the spell of Khan Saheb's music. The ecstatic tributes of a discerning western musician and critic after hearing the Ustad, prove how really exalted music overleaps all barriers and transports listeners into a transcendental world.

The critic writes: "I heard him melt half and quarter tones into one another with the effect of magic--- He was a conjurer of sounds...Who that has heard him can forget him. . . ! He not only sang sounds but he became every turn and twist in the song. The atmosphere became surcharged with a musical magic I have contacted nowhere else!".

The Kirana musical lineage came mostly from instrumentalists--chiefly Sarangiyas. After receiving his training from Kale Khan and Abdulla Khan, Khan Saheb went over to Baroda where he was appointed as a court-musician because of his great merit. After some years, he left Baroda for Bombay, and then went to Miraj. Wherever he went, his sweet voice and captivating style of singing won for him numerous admirers. From there, he proceeded to Hubli and Dharwar and stayed with his brother Abdul Haq. The two brothers often used to sing together. A notable pupil he acquired at this time was Rambhau or Sawai Gandharwa who later on, became one of his best disciples by sheer dint of practice. The Ustad was very punctilious about his early-morning daily practice, and Rambhau unfailingly practised with his conscientious guru every morning. A true "pilgrim of melody engaged in his eternal quest of swaras", Khan Saheb was constantly on the move. When he went to Patna, Roshanara's mother became his pupil.

In 1913 Abdul Karim Khan founded the Arya Sangeet Vidyalaya in Poona. It was a unique institution because the Ustad not only imparted whole-hearted musical training, but himself supported numerous poor and deserving students, took them on tours to give musical variety shows, and trained them up to play on various musical instruments. The ustad was an expert on many musical instruments, especially the Veena and the Sarangi. An expert in repairing musical instruments, he carried with him his set of tools for repairs everywhere because tuning the Tanpuras and perfecting their "Jawaaris" was almost an art in itself with him. The famous Sitar and Tanpura makers of Miraj revered him and looked up to his opinions for guidance.

A branch of this magnanimous institution was founded in Bombay in 1917, but it throve for only 2 or 3 years. When the School had to be closed down, Khan Saheb migrated to Miraj where he built a house of his own, and settled down at last. Though Miraj became the centre of his activities, he continued his musical tours all over the North and even into the far South. During his stay in Hyderabad and the Madras Presidency, his list of admirers and disciples in South India swelled and his popularity grew so much that whichever town he visited, people garlanded him and took him in a grand procession like a king. The ustad was greatly drawn to the music loving people of the South, and he was one of the early Hindustani musicians to kindle a great love for Hindustani music in the people of the South. He had, and still has, hundreds of admirers in the South. In spite of all the fame and adulation that he received, Abdul Karim Khan always lived frugally like a Sadhu, and like the Rishis of yore, Khan Saheb trained his disciples under the Gurukula system. He not only trained them thoroughly in music, but also bore the entire cost for feeding and clothing them out of his own earnings from concerts! Though a devout Muslim, and a devotee of Pir Sayyid Shamma Mira, a mystic saint (whose dargah is famous in Miraj), Khan Saheb was, like Kabir, a devout Hindu too, it is said. In his musical works he used to write '"OM TATSAT SAMAVEDAYA NAMAHA". Although born in a musical Muslim family (on 1lth Nov.1872), Abdul Karim took pride in his Hindu ancestors like Nayak DHONDU, a court-musician of Raja Man Singh of Gwalior (1486-1516 A.D). His first public concert was at the age of 11 (in 1893). Besides being such a great vocalist, Khan Saheb had also an amazing mastery over such varied instruments as Been, Sarangi, Jaltarang and Tabla. In Maharashtra great men like Lokamanya Tilak and Gopalakrishna Gokhale were drawn to his music. In the South, he became a favourite musician in the Mysore darbar, and his music was highly appreciated by great Karnatak musicians like Tiger Varadacharier, Muthiah Bhagawatar and Veena Dhanammal. He also created a stir by advancing the "Shruti Samvad" theory in collaboration with the British musicologist Mr. E. Clements, and is said to bave given a fine demonstration of 22 Shrutis (micro-tonal distances) with the help of 2 Veenas at a public function' presided over by Dr. C.V. Raman.

One of the most melodious classical musicians we have had, Abdul Karim Khan's music always created a sublime atmosphere. The soothing quality of his specially cultivated voice, and his reposeful style of singing were such that the singer as well as his listeners forgot themselves in a sort of "trance". Many of his musical heirs have surpassed him in technical virtuosity, but few have achieved "that degree of hypnotic effect" through music. Not only did he develop his own "Kirana" style of Khayal-badhut, but in his voice even the Thumri "shed its gossamer erotic undertones" and assumed instead "the character of a sad, pensive, and devout supplication". Many reputed musicians of today refer to Abdul Karim Khan Saheb as "Sachche swaron ke devata" (the master who sang perfect notes). He had cultivated a special way of voice production so that his sweet and melodious voice mingled indistinguishably with the drone of the Tanpura strings. This was acquired by him through years of strenuous "Mandra-sadhana", early morning practice for several hours in the lower notes. He stressed on voice culture in his pupils also; and even when he was at the zenith of fame, he never gave up this daily "mandra sadhana". Another outstanding quality of his music was its emotional element. Whatever he rendered, whether a Khayal, Thumri, Hori or Bhajan; the rendition "mirrored his whole inward being". While singing Khayals, he concentrated mostly on "ALAPI", and avoided "layakari", "boltans" etc, probably because he felt these might spoil the emotional atmosphere built up by him. Kans (grace-notes), and "gamakas" as in the Sarangi, and beautiful long unbroken "meends" (glides) as in the Veena, were some of the chief embellishments of his music. These and the emotion which he poured into his Thumris were so moving that often huge audiences wept when he sang some of his famous Thumris surcharged with feeling. The Gramaphone Company has done a great service by re-issuing many of his short items on a long-playing disc and striving to give us glimpses into his impassioned outpourings. Through these records of songs like "Jamuna ke Teer", "Piya Bina Nahi Awat Chain", "Gopala, Karuna kyon nahi--", "Piya ke milan ki aas" and "Naina raseeli", we can but have just flashes of those unforgettable hours a Khan Saheb Abdul Karim Khan transported his hypnotised audiences into a world of pure, sheer melody. On inspired days, he is said to have elaborated one Raga or a single Thumri for hours, and kept his audience spell-bound throughout. Being fond of Alap-ang, Abdul Karim Khan always preferred to sing expansive ragas like Lalit, Jaunpuri, Marwa, Malkauns, Todi, Darbari and so on. Among his chief disciples, Pdt. Balkrishnabuwa Kapileswari deserves special praise for running a school, "Shree Saraswati Sangeet Vidyalaya" carrying on the traditions of his great Ustad. In 1963 he published SHRUTIDARSHAN, a valuable research-work in music incorporating the findings of his guru and his own. The book won for him 2 important awards.

The traditions of generosity and hospitality that Abdul Karim Khan set up at the munificent annual "Urus" of Mirasaheb in Miraj (where he used to feed hundreds of fakirs and encourage musicians lavishly) have been kept up by his devoted widow BANUBAI, and disciples like Hirabai. Numerous were the poor music-students whom Khan Saheb had supported and trained in music. Another example of his generosity is that during his musical tours, he always took his accompanists also with him in the same compartment.

Although frail-looking, Khan Saheb maintained excellent health through regular exercises, disciplined habits, and frugal living. His photographs show him as a tall, slim person dressed immaculately in a black achkan, a cane in hand, a typical moustache and a red gold-bordered turban, and most striking of all, his dreamy eyes about which Mr K. Subbarayan narrates an interesting little anecdote in the Bhavan's Journal (1972):

Mystified by the dreamy eyes of the Khansaheb, Mrs Annie Besant had once discreetly enquired of a disciple whether the master was addicted to any drug. "Indeed", came the reply, "He is very much addicted to the intoxication of music!".

In 1937 Khan Saheb went down to South India to give music soirees in various parts of the Madras Presidency. A huge crowd of admirers saw him off at the Madras Station and nearly smothered him with garlands. He was on his way to Pondicherry with some friends. Feeling very unwell and restless, he detrained at one of the intermediate stations to take some rest. Before lying down, he sang his prayers set in Rag Darbari and then lay down to sleep for ever! It was a most unexpected end and yet so like this great and good artiste to round off his earthly existence with a tuneful bhajan! At the loving insistence of his admirers, his body was taken in a special car to Madras, and thence to Miraj, crowds paying their last homage to the departed singer through out the journey. At Miraj, Banubai gave him a magnificent funeral. Memorial programmes to this great musician are held every year in the month of August.

See also: http://www.itcsra.org/tribute.asp?id=1

Thursday, 15 August 2013

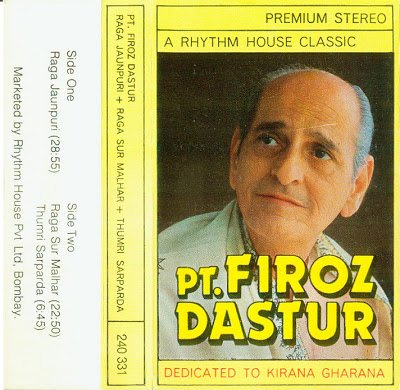

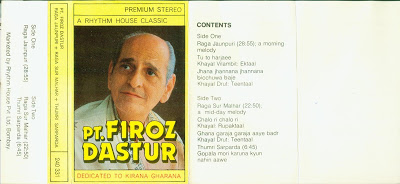

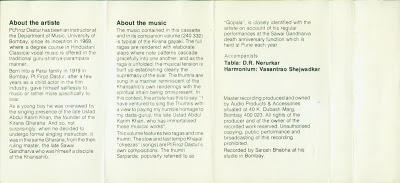

Firoz Dastur (1919-2008) - Dedicated to Kirana Gharana - Cassette from India

Thanks to Ambrose Bierce for sharing this cassette.

A Tribute to Pandit Firoz Dastur

Having passed away on

May 9, Pandit Firoz Dastur, the doyen of the Kirana Gharana and a disciple of

Sawai Gandharv, leaves behind a legacy that is hard to equal. Having commanded a

singing career of six decades, Dastur's music touched many souls and moved

several hearts.

As gratitude for his teaching and a celebration of his

luminosity, Shrikant Deshpande, one of Dastur's disciples along with disciple

Girish Sanzgiri and Srinivas Joshi, son of Pandit Bhimsen Joshi, will be

organising a tribute to Pandit Firoz Dastur on Saturday, May 17 at Pudumjee

Hall, Maratha Chamber of Commerce, Industries and Agriculture, Tilak Road

between 6pm and 8pm. Organised by Arya Sangeet Prasarak Mandal, which also

organises the Sawai Gandharv Sangeet Mahotsav, the event being open to the

public, will see 15-minute performances by each of the artistes followed by an

eulogy to Dastur.

Recalling fond memories of his guru, Deshpande says, “Noble

of character, the disciples of Panditji rather than sharing a guru-shishya

relationship were great friends of his. And he was the only guru that I know of

who wouldn't even hesitate from apologising to his own disciple on the

occurrence of a mistake.”

Dastur was also one of the pioneers of the Sawai

Gandharv and has participated in almost every festival since its inception, his

gopala being a consistent favourite there. Anand Deshmukh, who has been

compering Sawai Gandharv since 20 years, relates of his gentleness of mien and

his lightheartedness. “The stalwart, inspite of being such a tall artist, was

down-to-earth and sans any grandiosity.” He brings to memory an opportune

instance when Deshmukh had the chance to interview Dastur at his house on Grant

Road in Mumbai and several chats with him in green rooms at Sawai Gandharv. “He

always said that his genteel performances are not his, but instead it is his

guru who is playing through him,” Deshmukh relates of Dastur, “He was also

always respectful of young artists and always listened to their music.” He also

recalls of how when Dastur jokingly denied the audience the pleasure of his

rendition of gopala, through shouts of gopala, the audience moved him into

singing it for them once again.

Everyone remembers Dastur's dulcet, gentle

voice, as does singer Neena Faterpekar. ”A softspoken human being, his music

resonated the same characteristics,” she says, “I have been seeing him since I

was a child as he knew both of my grandmothers and we had nice family moments

together.” His study of voice culture, aalaps and the styles of Kirana Gharana

were great. “He always encouraged my music and would always sit in the front row

during my concerts. Though he gave me tips, he always enthused me to pursue and

continue with my style of music,” she says emotionally.

Dastur, having been a

father figure to him, Srinivas Joshi was always astounded to be in the presence

of Dastur and how he, inspite of his greatness, possessed such rare humility and

mingled with his juniors. Having grown up listening to Dastur, Joshi says that

his loss will be paramount to music and to Kirana Gharana. “His devotion to his

guru and to his parampara is something everyone should work to imbibe,” says

Joshi.

Kirana Gharana has lost a great exponent and many artistes have lost a

friend and a mentor. Though without his presence, Sawai Gandharv wouldn't be the

same, his company and his devotion to music would be treasured and perhaps that

is what Dastur will see as an apt homage.

Friday, 9 August 2013

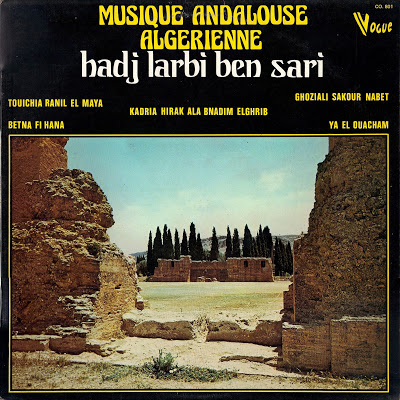

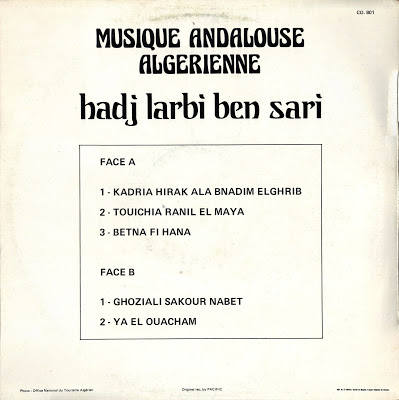

Hadj Larbi Ben Sari (1867-1964) - Musique Andalouse Algérienne - LP from Algeria

Great representative of the Arabo-Andalusian tradition of Tlemcen, the so-called Gharnati style.

Side 1:

1. Kadira Hirak Ala Bnadim Elghrib (El Ghrib)

2. Touichia Ranil (more correct: Touchia Raml) El Maya

3. Betna Fi Hana

Side 2:

1. Ghoziali Sakour Nabet

2. Ya El Ouacham

1. Ghoziali Sakour Nabet

2. Ya El Ouacham

Cheikh Larbi Bensari (né à Tlemcen en 1867- mort à

Tlemcen en 1964) est le maître du gharnati et du hawzi tlemcénien. C'est

l'artiste le plus en vue de l'école de Tlemcen au début du xxe

siècle.

Larbi Bensari est issu d'une famille tlemcénienne modeste. Il fut recruté

en qualité d’apprenti coiffeur, chez un grand maître de musique

andalouse Mohammed Benchaabane dit Boudelfa, qui dirigeait un orchestre; mais si

Cheikh el Arbi était un piètre élève dans la profession de coiffeur, il

excellait, par contre, dans la musique andalouse que lui enseignait son maître;

le jeune Sari, élève studieux, animé d’une très grande volonté, apprit vite à

jouer de tous les instruments, et particulièrement le r’beb et l'alto. Boudelfa,

reconnaissant quelque temps plus tard que son élève est devenu un virtuose, lui

confia la direction de son orchestre.

Initié par Makchiche, M'naouar et

Boudelfa, il a su mettre en pratique les ressources de son étonnante mémoire, de

son intelligence musicale et de sa volonté pour réussir à s'imposer comme l'un

des meilleurs exécutants de la ville. «Sous le direction attentive de

connaisseurs, nombreux à l'époque, autant que censeurs avertis et sévères et qui

ne font grâce d'aucun faux pas, il réunira tous les suffrages. Sa maîtrise et

son talent feront très vite de lui un chef d'orchestre incontestable. »

Sa

palette allait du hawzi au 'arûbi, au madh, et du gharnati au ça'nâa, il

s'intéressa également au gharbi. Il accordait cependant une place prépondérante

à la musique classique ça'nâa. Il laissera à sa mort plusieurs noubas sur les 24

que compte la musique de Zyriab.

L'artiste a

représenté l'Algérie en 1900 lors de l'Exposition Universelle de Paris. A

l'invitation de Si Kaddour Benghabrit, il donnera un concert à l'occasion de

l'inauguration de la Grande Mosquée de Paris en 1926. En 1932, il est de nouveau

sollicité pour représenter son pays au Congrès de musique arabe du

Caire.

Cheikh Larbi Bensari constitue une pièce maîtresse dans l'analyse de

la sociologie de l'art musical à Tlemcen du fait même que sa technique

pédagogique d'apprentissage et sa rigueur d'interprétation établit le rapport

d'allégeance culturelle de Tlemcen vis-à-vis de Grenade.

Wednesday, 7 August 2013

Hamza Shakkur (1947-2009) - Munshid from Damascus, Syria - Chamiaate - Chant Soufi

Beautiful cassette by the great munshid from Damascus, Syria

Sheikh Hamza Shakkur: Syrian master of mystical song

by Suleman Taufiq24 February 2009

Bonn, Germany - Sheikh Hamza

Shakkur, a well-known interpreter of traditional Arab music, died in Damascus on

4 February 2009 at the age of 65.

The way in which Sheikh Hamza Shakkur

could lull his listeners into a trance-like state by grace of his singing alone

had to be seen to be believed. He possessed not only vocal talent, but also a

powerful, sonorous and all-embracing voice capable of playing counterpart to an

orchestra and filling an entire room.

His musical intuition was borne of

a spiritual power that drew listeners into the mystical tradition of Sufism. His

bass voice with its richly rounded timbre made him one of the most famous

singers in the Arab world.

Shakkur was born in Damascus in 1944. At an

early age he received a thorough training in Qur’anic recitation according to

the Syrian tradition. His father was the muezzin at the local mosque who taught

Shakkur the basics of spiritual recitation. At the age of ten, Shakkur assumed

this role, thereby becoming his father’s successor.

Although he never

learned to read music, he built up a repertoire comprising thousands of songs by

learning lyrics and melodies by heart.

Among the mystics of the Sufi

community he began studying the hymns of mystical love, a form of expression

that is still highly respected in Arab society. Having studied the entire

spiritual repertoire of Islam he was in much demand as a singer. He also made

numerous recordings for the radio.

Later he became choirmaster of the

Munshiddin (a group of individuals who recite the Qu’ran) at the Great Mosque of

Damascus and performed at official religious ceremonies there, which made him

immensely popular in Syria. The Great Mosque in Damascus is one of the most

sacred sites in Islam.

Shakkur belonged to the traditional Damascus

school of music. He felt a close bond with the Mevlevi Order, the community of

“whirling dervishes”, and strove to preserve the continuity of their repertoire.

This community is known for its whirling dance ritual, the epitome of Eastern

mysticism. Dressed in wide swinging, bell-shaped white skirts and camel-coloured

felt hats, they whirl to classical music and chanting.

Sufis believe that

life is an eternal circular motion out of which everything arises and in which

everything exists and passes. Their ritual dance symbolises the spiritual source

of Sufi mysticism. If the dancer goes into a trance, he experiences himself as

suspended in God’s love, as part of this eternal divine movement.

This

mystical brotherhood met in lodges, and preserved the original songs, which were

divided into suites, modes and rhythms.

The Great Umayyad Mosque in

Damascus has its own specific vocal repertoire in which sacred suites are known

as nawbat, a term originally used for secular songs that were written in Arab

Andalusia and became known there as muwashahat.

Reciters such as Shakkur,

typically accompanied by a choir, took from the repertoire of the mosque the

mention of God’s 99 divine names and the birth of the Prophet Muhammad and

chanted them in a powerfully expressive manner, rigorously mobilising rhythm to

support their songs. In this way, he succeeded in gradually putting gathered

listeners into a trance or a state of meditation.

In 1983 Shakkur and

French musician Julien Weiss founded the Al Kindi ensemble, through which he

succeeded in introducing this music to Europe and America.

The ensemble

specialised in music from Arab-Andalusia and its repertoire covered both

religious and secular themes. Its interpretations were heavily steeped in

tradition. Weiss created an Arab musical ensemble with the Arab lute, oud, ney,

kanun and a variety of rhythm instruments.

Shakkur selected songs with

very diverse rhythms and melodies that impressively demonstrated his musical

phrasing and improvisational talent. Particular emphasis was placed on

preserving the unity of the sequence of songs and their musical mode as well as

on playing songs in the traditional manner.

Shakkur was a religious man

and had a religious title. Nevertheless he sang not only religious but also

secular songs. He followed the tradition of the Sufi community for whom music is

an integral part of religious ceremonies and the medium through which the human

soul comes closer to the divine.

Shakkur preferred the vocal

improvisation of Arabic music. He mastered the art of Arab emotional singing

like few others and understood how to adjust intuitively to the emotions of each

audience in order to captivate and enthral it.

Source: Qantara.de, 17

February 2009, www.qantara.defrom: http://www.commongroundnews.org/article.php?id=24910&lan=en&sp=0

Sheikh Hamza Shakkur Talks About Sufi Music

By Sami Asmar

Sheikh Hamza

Shakkur's voice emanates spiritual power that draws listeners into the mystical

tradition of Sufism. Born in Damascus in 1947, Sheikh Shakkur is a quranic

reader and hymnist. He is also the choirmaster of the Munshiddin (reciters) of

the Great Mosque in Damascus and serves at official religious ceremonies in

Syria, where he is immensely popular. His bass voice with its richly rounded

timbre has made him one of the foremost Arab vocalists. Shakkur is the disciple

of Said Farhat and Tawfiq al-Munajjid and feels the responsibility to assure the

continuity of the repertoire in the Mawlawiyya (Mevlevi in Turkish)

order.

Damascus was the capital of the Ummayyad dynasty and a principal stage

in the pilgrimage to Mecca. The Sufi mystical brotherhood known as Mawlawiyya

met in places known as zawiya and adopted the original chants grouped in suites

(waslat) in particular modes (maqamat) and rhythms (iqaat). The Great Ummayyad

Mosque of Damascus possesses a specific vocal repertoire, where sacred suites

are known as a nawbat, a term originally used for the secular songs developed in

Arab Andalusia known as muwashshat. Typically accompanied by a choir, a vocalist

such as Sheikh Hamza Shakkur extracts from the repertoire of the mosque the

naming of God (dhikr) and the birth of the prophet (mawlid) in a serene

expression that has a rigorously organized rhythm. Thus the vocalist

progressively leads the assembly into a trance or a state of meditation

(ta'ammul).

In the early ninth century, when the Muslim mystics organized

their Sufi brotherhoods, they adopted music for their meditation as a way of

reaching the state of ecstasy, a source of new vigor to the body and soul. In

Sufism,sama' denotes the tradition of listening in a spiritual fashion to music

of all forms. This suggests that the act of listening is spiritual, without the

music or poetry being necessarily religious in content. The major preoccupation

of the mystics was to give the ecstasy real content and the music true

meaning.

The Mawlawiyya order was founded in Konya, Anatolia, by the Persian

poet Jalal al-Din al-Rumi (1207-1273). Although the ritual is primarily

associated with Turkey, local traditions have existed in Syria, Egypt, and Iraq

since the 16th century. The Mawlawiyya of Damascus are very few and have been

threatened with closure on many occasions. The personal prestige of Sheikh Hamza

Shakkur has rescued them, for he has reached celebrity status that has allowed

him to generate support for the small group.

We met with the Sheikh, who

led the Whirling Dervishes of Damascus in a great concert in Los Angeles,

accompanied by al-Kindi Ensemble.

Asmar: How do you describe Sufism to

Westerners?

Shakkur: This is a very difficult question but nothing is too

difficult for a Sufi. Tassauf is only for those with convictions about the

belief in God and his prophet. Trust in God must be blind. When encountering

Westerners who may not have reached the spiritual level required for full

understanding, there are seven languages that the Sufi can use to communicate

with them. The Sufi practitioner needs to be advanced and highly capable in

order to communicate via these seven languages. First is the Arabic tongue, the

language of the Quran, which is universally appreciated as a beautiful language.

Second is the language of music, which is also universal, needless to say. Third

is the language of the eyes; the eye is the window to the soul. Fourth is

language of silence; this is an important one for a hymnist, reader or musician,

for the appropriate length rest at the appropriate time is part of the

communication scheme. The language of silence is also manifested in the saying

that silence is the sign of agreement. For example, in an old tradition, when a

man proposes marriage to a woman, her silence is taken as an acceptance. Fifth

is the expression of feelings. Sixth is physical expressions (taabir) or body

language. Seventh is the language of the soul, as Islam is as much a spiritual

religion as it is practical. The key to all these is that they have to come from

the heart, truly, or else the communication fails.

Asmar: What does the

whirling of the Mawlawiyya signify?

Shakkur: It is important to note that the

Mawlawiyya is only one of the expressions of Sufism, not its only

representation. In the Dhikr of God, one can be moved to stand, sit, lean,

whirl, rotate the neck, become silent or whatever other physical expression

comes as a first reaction. The whirling of the Mawlawiyya is inspired by the

rotation of the Earth and cycle of blood circulation in the body. Circular

motion has great significance in the wisdom of the creator.

Asmar: What

distinguishes the Ummayyad mosque from other mosques?

Shakkur: The Mosque of

Bani Ummayya has very distinctive hymns and melodies, even the call to prayer

(azan). Historically speaking, Salaheddine al-Ayyubi, several centuries ago,

encouraged the people to sing specific chants in this mosque as he prepared them

to battle the crusaders, and that started a long tradition of wonderful hymns in

the form of nawbat. But this was not formally organized until the scholar Sheikh

Abd al-Ghani al-Nabulsi who, inspired by al-Ayyubi, built on the tradition using

his own amazing spirituality and added lyrics and tunes and eventually set up

guidelines for the repertoire of the Ummayyad Mosque. He also introduced musical

instruments. Before him, they only used drums.

Asmar: Are instruments allowed

inside the Mosque?

Shakkur: No, not inside the mosque, but in the courtyard

and the Mawlawiyya zawiya.

Asmar: What was the accepted use of these

instruments?

Shakkur: Sheikh al-Nabulsi wrote a book on the proper use of

music in our tradition called "Al-Dalalat Fi Sama' Al-Alat" (The Signs of

Listening to Instruments). He stressed that musical instruments have good uses

to praise God and express spirituality and bad uses as a tool of seduction or

material gain. He also composed two calls to prayer (azan) that are different

from the standard ones you hear elsewhere. He created a group azan in which a

soloist calls Allah Akbar (God is Great) and a choir repeats after him in a

special melody. He is also credited for a different tune for the so-called Azan

al-Imsak, which is the call to prayer 10 minutes before the sunrise azan. We

also chant the azan in the maqamat siqah and Bayyati as well as the standard

Hijaz and Rast maqamat known throughout the Islamic world. Damascus is unique in

having options for four maqamat for the azan.

Asmar: Are you also saying

there are extra azan (calls to prayer) beyond the standard times?

Shakkur: We

have tarahim, special prayers between azans. Also every tower (maazanah) in the

mosque has its own version of the azan. It is quite a sophisticated

arrangement.

Asmar: What is the relationship between the Andalusian Arab

heritage and the repertoire of the Ummayad Mosque?

Shakkur: There is a clear

link between the two. Many traditions were carried back to Damascus through

North Africa where they prospered more in the Mosque community than elsewhere.

We even use the same terminology, such as nawba, that you still hear in North

African classical music of muwashshat. What has developed in the repertoire of

the Ummayad Mosque, however, is unique and clearly distinct from the Andalucian

or North African traditions despite the historical connections.

This article

appeared in Vol. 7, no. 36 (Summer 2001).from: http://www.aljadid.com/content/sheikh-hamza-shakkur-talks-about-sufi-music-0

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

%20-%20front.jpg)

%20-%20back.jpg)

%20-%20front.jpg)

%20-%20back.jpg)

%20-%20front.jpg)

%20-%20back.jpg)

%20-%20front.jpg)

%20-%20back.jpg)

%20-%20front.jpg)

%20-%20back.jpg)